[caption id="attachment_3750" align="aligncenter" width="1014"] File Picture[/caption]

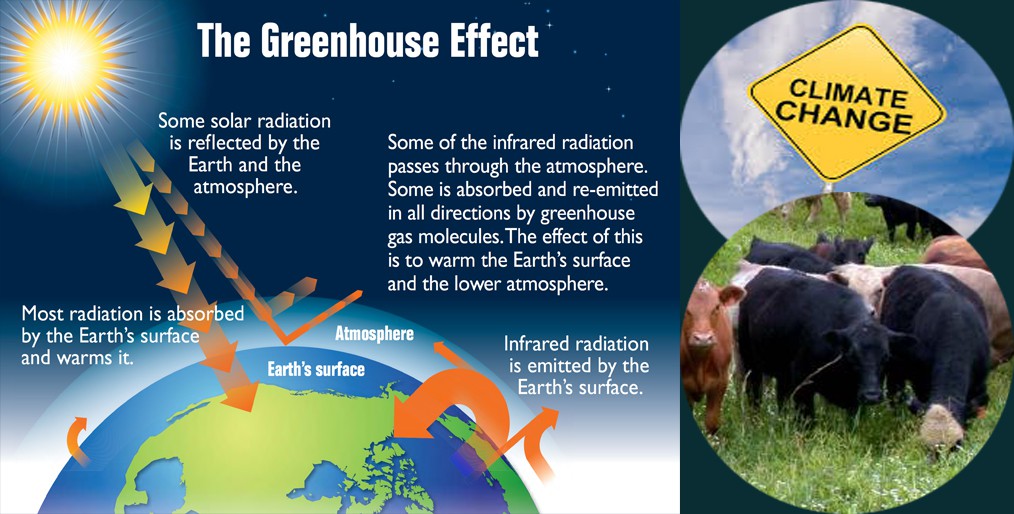

Climate Change is the defining issue of our time and we are at a defining moment. From shifting weather patterns that threaten food production, to rising sea levels that increase the risk of catastrophic flooding, the impacts of climate change are global in scope and unprecedented in scale. Without drastic action today, adapting to these impacts in the future will be more difficult and costly. Scientists are constantly trying to develop from this condition.

The cows grazing peacefully in the vicinity of New Zealand’s farming science research institute AgResearch look much like any other. They plod slowly around the pastures, heads bowed as they tear up mouthfuls of grass and let out soft, low moos.

But some of these animals are not like the cattle you might find on other farms. Away from view, inside the hard-working stomachs of these cows, an experiment that could potentially change the planet is taking place.

They have been given a vaccine against certain gut microbes that are responsible for producing methane as the animals digest their food. Methane is one of the most egregious of greenhouse gases, roughly 25 times more potent at trapping heat than carbon dioxide.

AgResearch’s aim is to develop this vaccine, along with other anti-methane methods, in an effort to allow us to continue eating meat and dairy products while lessening the impact the livestock industry has on the environment. Beef without blame, you might say; and cheese with a clear conscience.

Estimates vary, but livestock are reckoned to be responsible for up to 14% of all greenhouse emissions from human activities. Alongside carbon dioxide, farming generates two other gases in large quantities: nitrous oxide from the addition of fertilizers and wastes to the soil, and methane. The latter is largely belched out by ruminants – principally sheep and cattle – and accounts for more than a third of the total emissions from agriculture. The average ruminant produces 250-500 liters of methane a day. Globally, livestock are responsible for burping (and a small amount from farting) the methane equivalent of 3.1 gigatons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere annually.

But the scientists at AgResearch hope it may be possible to reduce the contribution livestock farming is making to global warming.

Their approach builds on work by Sinead Leahy, a microbiologist at AgResearch who is currently on secondment to the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre. The methane produced by ruminants comes from some 3% of the vast number of microbes that live in the rumen, the first section of the gut. The guilty organisms belong to an ancient group called the archaea, and they are capable of living in environments where there is no oxygen.

Through a process known as enteric fermentation, these microbes decompose and ferment the plant materials eaten by the animals, producing methane as a byproduct. To release the pressure that can build up as this gas is produced the animals then burp it out.

To weed out the bacteria responsible, however, Leahy and her colleagues had to find a way of reproducing the oxygen-free conditions of the rumen in their laboratory. Using DNA technology, they were then able to sequence the genomes of some of the key species.

“Understanding what makes these microbes different from other types that are also important for ruminant digestion is essential,” says Leahy. “Through our research we were able to look across the different types of gene sequence [in the microbes] and pick out targets [shared] across all varieties of methanogen. These then became the top targets for the development of a vaccine.”

This work allowed the team at AgResearch to systematically design vaccines that targeted several microbe species at the same time.

“There are about 12 or 15 species in the subset of archaea we’ve tried to target,” says Peter Janssen, principal investigator of the methane mitigation program at AgResearch, who has identified various methane-producing microbes in the rumen of sheep and cows. Given by injection, the vaccine is designed to stimulate the animals’ output of anti-archaea antibodies in their saliva, which is then carried into the rumen as the animals swallow.

So far only a small number of cows and sheep have been given the vaccine in trials by the AgResearch team. But the team has picked up a good level of antibody in the saliva and also in the rumen, and antibodies have been recovered from faeces as well, according to the Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium, the major funder of the research since 2006. Having shown that vaccinated animals are actually making the antibody, they’re now trying to demonstrate that this does indeed suppress the formation of methane.

To test this, animals must spend time in a respiratory chamber – a large transparent box, sealed except for a flow of fresh air. Stale air leaving the box is sampled for its methane content.

The researchers are also attempting to make measurements outside the laboratory too to better replicate what goes on in the field. One approach is to use a modified feeding trough into which the animal has to put its head to eat. “While their noses are in the feeding trough a gadget inside it can sample their breath,” says Janssen. Even more cunning is a device that can be strapped on to an animal’s back. “It has a little plastic tube that finishes just above the animal’s nose. As the animal exhales the device sucks up a sample of its breath.”

Neither technique compares for accuracy with the respiration chamber, but both serve to give a good idea of what’s going in large numbers of animals. But definitive proof that vaccination cuts the amount of methane belched out by cows is still lacking.

Janssen and his colleagues do know from previous work using drugs that suppressing the methanogens yields the promised reduction. But Janssen and Leahy are not the first to try making a vaccine against methanogens, the term for any microbe manufacturing methane. Some Australian scientists had a go in the 1990s, but were unsuccessful. The AgResearch Team is confident their approach, informed by genetics, will yield better results.

But vaccination isn’t the only idea for cleaning up cows’ breath. Animals vary in their output of methane, and some at least of this variation is attributable to genetic differences. Eileen Wall, head of research at Scotland’s Rural College, explains that this offers scope for selective breeding for animals that produce less methane. She sees this not as something to be done in isolation, but as part of a wider breeding programs to develop healthier and more efficient sheep and cows – both these attributes also reduce the greenhouse gases generated per unit of meat and milk.

“Over the past 20 years we’ve already reduced the environmental footprint of milk and meat production in the UK by 20%,” she says. Breeding for low methane would simply be an add-on to existing programs. She and her colleagues are experimenting with methods of doing just this. Find More…

Source: Online/SZK

File Picture[/caption]

Climate Change is the defining issue of our time and we are at a defining moment. From shifting weather patterns that threaten food production, to rising sea levels that increase the risk of catastrophic flooding, the impacts of climate change are global in scope and unprecedented in scale. Without drastic action today, adapting to these impacts in the future will be more difficult and costly. Scientists are constantly trying to develop from this condition.

The cows grazing peacefully in the vicinity of New Zealand’s farming science research institute AgResearch look much like any other. They plod slowly around the pastures, heads bowed as they tear up mouthfuls of grass and let out soft, low moos.

But some of these animals are not like the cattle you might find on other farms. Away from view, inside the hard-working stomachs of these cows, an experiment that could potentially change the planet is taking place.

They have been given a vaccine against certain gut microbes that are responsible for producing methane as the animals digest their food. Methane is one of the most egregious of greenhouse gases, roughly 25 times more potent at trapping heat than carbon dioxide.

AgResearch’s aim is to develop this vaccine, along with other anti-methane methods, in an effort to allow us to continue eating meat and dairy products while lessening the impact the livestock industry has on the environment. Beef without blame, you might say; and cheese with a clear conscience.

Estimates vary, but livestock are reckoned to be responsible for up to 14% of all greenhouse emissions from human activities. Alongside carbon dioxide, farming generates two other gases in large quantities: nitrous oxide from the addition of fertilizers and wastes to the soil, and methane. The latter is largely belched out by ruminants – principally sheep and cattle – and accounts for more than a third of the total emissions from agriculture. The average ruminant produces 250-500 liters of methane a day. Globally, livestock are responsible for burping (and a small amount from farting) the methane equivalent of 3.1 gigatons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere annually.

But the scientists at AgResearch hope it may be possible to reduce the contribution livestock farming is making to global warming.

Their approach builds on work by Sinead Leahy, a microbiologist at AgResearch who is currently on secondment to the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre. The methane produced by ruminants comes from some 3% of the vast number of microbes that live in the rumen, the first section of the gut. The guilty organisms belong to an ancient group called the archaea, and they are capable of living in environments where there is no oxygen.

Through a process known as enteric fermentation, these microbes decompose and ferment the plant materials eaten by the animals, producing methane as a byproduct. To release the pressure that can build up as this gas is produced the animals then burp it out.

To weed out the bacteria responsible, however, Leahy and her colleagues had to find a way of reproducing the oxygen-free conditions of the rumen in their laboratory. Using DNA technology, they were then able to sequence the genomes of some of the key species.

“Understanding what makes these microbes different from other types that are also important for ruminant digestion is essential,” says Leahy. “Through our research we were able to look across the different types of gene sequence [in the microbes] and pick out targets [shared] across all varieties of methanogen. These then became the top targets for the development of a vaccine.”

This work allowed the team at AgResearch to systematically design vaccines that targeted several microbe species at the same time.

“There are about 12 or 15 species in the subset of archaea we’ve tried to target,” says Peter Janssen, principal investigator of the methane mitigation program at AgResearch, who has identified various methane-producing microbes in the rumen of sheep and cows. Given by injection, the vaccine is designed to stimulate the animals’ output of anti-archaea antibodies in their saliva, which is then carried into the rumen as the animals swallow.

So far only a small number of cows and sheep have been given the vaccine in trials by the AgResearch team. But the team has picked up a good level of antibody in the saliva and also in the rumen, and antibodies have been recovered from faeces as well, according to the Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium, the major funder of the research since 2006. Having shown that vaccinated animals are actually making the antibody, they’re now trying to demonstrate that this does indeed suppress the formation of methane.

To test this, animals must spend time in a respiratory chamber – a large transparent box, sealed except for a flow of fresh air. Stale air leaving the box is sampled for its methane content.

The researchers are also attempting to make measurements outside the laboratory too to better replicate what goes on in the field. One approach is to use a modified feeding trough into which the animal has to put its head to eat. “While their noses are in the feeding trough a gadget inside it can sample their breath,” says Janssen. Even more cunning is a device that can be strapped on to an animal’s back. “It has a little plastic tube that finishes just above the animal’s nose. As the animal exhales the device sucks up a sample of its breath.”

Neither technique compares for accuracy with the respiration chamber, but both serve to give a good idea of what’s going in large numbers of animals. But definitive proof that vaccination cuts the amount of methane belched out by cows is still lacking.

Janssen and his colleagues do know from previous work using drugs that suppressing the methanogens yields the promised reduction. But Janssen and Leahy are not the first to try making a vaccine against methanogens, the term for any microbe manufacturing methane. Some Australian scientists had a go in the 1990s, but were unsuccessful. The AgResearch Team is confident their approach, informed by genetics, will yield better results.

But vaccination isn’t the only idea for cleaning up cows’ breath. Animals vary in their output of methane, and some at least of this variation is attributable to genetic differences. Eileen Wall, head of research at Scotland’s Rural College, explains that this offers scope for selective breeding for animals that produce less methane. She sees this not as something to be done in isolation, but as part of a wider breeding programs to develop healthier and more efficient sheep and cows – both these attributes also reduce the greenhouse gases generated per unit of meat and milk.

“Over the past 20 years we’ve already reduced the environmental footprint of milk and meat production in the UK by 20%,” she says. Breeding for low methane would simply be an add-on to existing programs. She and her colleagues are experimenting with methods of doing just this. Find More…

Source: Online/SZK

Comment Now